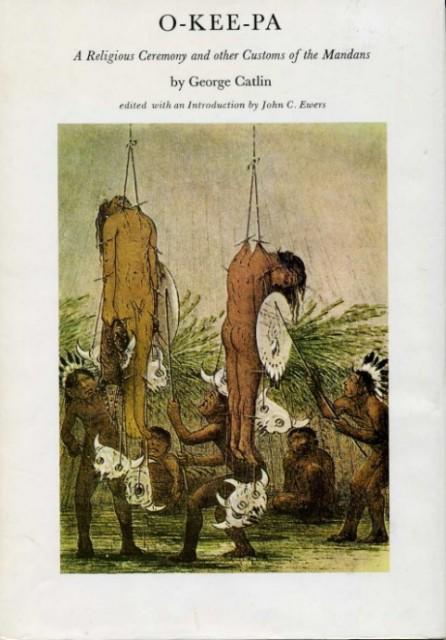

Many people know that the O-Kee-Pa - is hanging by 2 hooks in the chest, but few people are aware of what exactly that means. I would like to finally dispel all doubts and publish adequate information using American ethnologist George Catlin's article.

But first about Catlin himself.

Catlin was born and raised in Wilkes - Barre, Pennsylvania . He was fond of hunting, fishing and was interested in Indian artifacts. His fascination with Native Americans initiated by his mother, who told him stories about the Western Frontier and how it was captured by a tribe when she was a young girl. Years later a group of Native Americans passed through Philadelphia dressed in colorful costumes and made impression of yong boy .

He began his journey in 1830, when he accompanied General William Clark on a diplomatic mission to the Mississippi River, Indian Territory. After that, he made five trips between 1830 and 1836 years, eventually visiting fifty tribes. He went up the Missouri River over 3000 km to Fort Union, where he spent several weeks among indigenous people still relatively untouched by European civilization. He visited eighteen tribes, including Pony, Omaha and Ponca - the south and the north - Hidatza, Cheyenne, Crow, Assiniboine, Blackfeet and Mandan, which will be discussed. There, on the edge of the border, he created the most vivid and penetrating portraits of his career.

Mandan tribe was almost wiped out by smallpox in 1837, but some of them survived and continued to practice the O-Kee-Pa up to 1890. Catlin visited the Indians in their last happy years and spent with them most of the summer in 1832. While his impressions were fresh, he wrote the article for the New York newspaper, and nine years later it expanded and included in illustrated version.

O-Kee-Pa

During the summer of 1832 I made two visits to the tribe of Mantlan Indians, all living in one village of earth-covered wigwams, on the west bank of the Missouri River, eighteen hundred miles above the town of St. Louis.

Their numbers at that time were between two and three thousand, and they were living entirely according to their native modes, having had no other civilized people residing amongst them or in their vicinity, that we know of, than the few individuals conducting the Missouri Fur Company’s business with them, and living in a trading-house by the side of them. …

The Mandans, in their personal appearance, as well as in their modes, had many peculiarities different from the other tribes around them. In stature they were about the ordinary size; they were comfortably, and in many instances very beautifully clad with dresses of skins. Both women and men wore leggings and moccasins made of skins, and neatly embroidered with dyed porcupine quills. Every man had his “tunique and manteau” of skins, which he wore or not as the temperature prompted; and every woman wore a dress of deer or antelope skins, covering the arms to the elbows, and the person from the throat nearly to the feet.

In complexion, colour of hair, and eyes, they generally bore a family resemblance to the rest of the American tribes, but there were exceptions, constituting perhaps one-fifth or one-sixth part of the tribe, whose complexions were nearly white, with hair of a silvery-grey from childhood to old age, their eyes light blue, their faces oval, devoid of the salient angles so strongly characterizing all the other American tribes and owing, unquestionably, to the infusion of some foreign stock.

Amongst the men, practised by a considerable portion of them, was a mode peculiar to the tribe, and exceedingly curious—that of cultivating the hair to fall, spreading over their backs, to their haunches, and oftentimes as low as the calves of their legs; divided into flattened masses of an inch or more in breadth, and filled at intervals of two or three inches with hardened glue and red or yellow ochre. …

The Mandans (Nu-mah-ká-kee, pheasants, as they called themselves) have been known from the time of the first visits made to them to the day of their destruction, as one of the most friendly and hospitable tribes on the United States frontier; and it had become a proverb in those regions, and much to their credit … “that no Mandan ever killed a white man.”

I was received with great kindness by their chiefs and by the people, and afforded every facility for making my portraits and other designs and notes on their customs; and from Mr. [James] Kipp, the conductor of the Fur Company’s affairs at that post, and his interpreter, I was enabled to obtain the most complete interpretation of chiefly all that I witnessed.

I had heard, long before I reached their village, of their “annual religious ceremony,” which the Mandans call “O-kee-pa.” … I resolved to await its approach, and in the meantime, while inquiring of one of the chiefs whose portrait I was painting, when this ceremony was to begin, he replied that “it would commence as soon as the willow-leaves were full grown under the bank of the river.”…

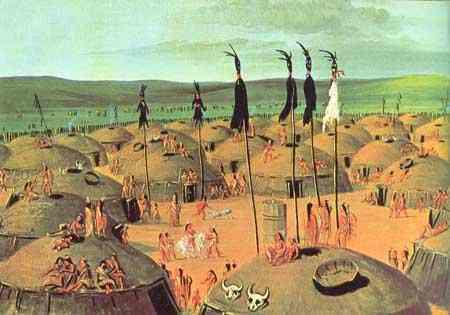

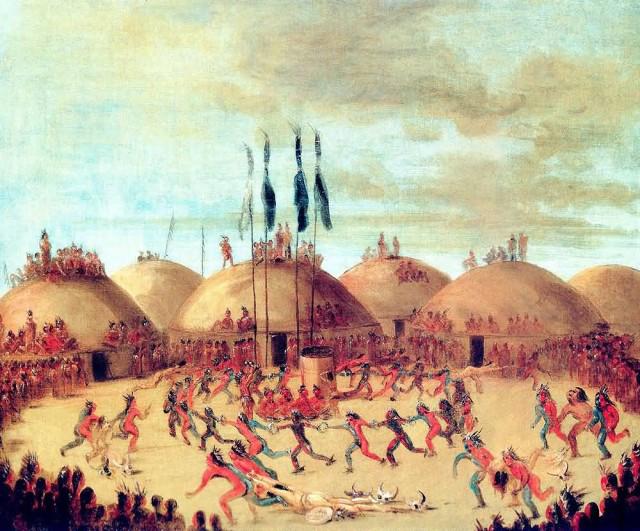

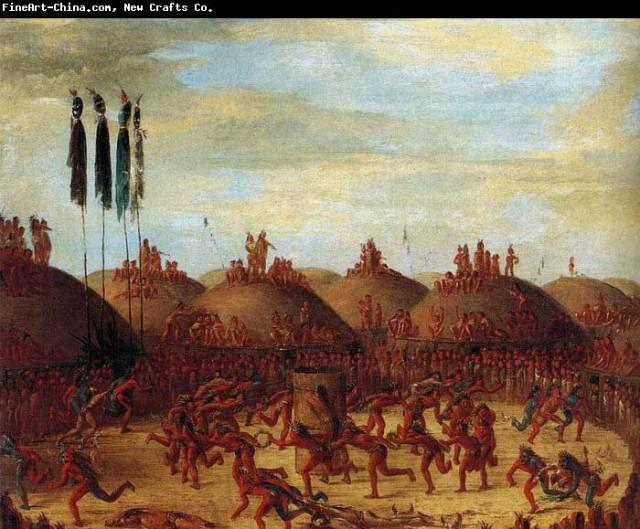

As I have before said, these people all lived in one village, and their wigwams were covered with earth--they were all of one form; the frames or shells constructed of timbers, and covered with a thatching of willow-boughs, and over and on that, with a foot or two in thickness, of a concrete of tough clay and gravel, which became so hard as to admit the whole group of inmates, with their dogs, to recline upon their tops. These wigwams varied in size from thirty to sixty feet in diameter, were perfectly round, and often contained from twenty to thirty persons within.

The village was well protected in front by a high and precipitous rocky bank of the river; and, in the rear, by a stockade of timbers firmly set in the ground, with a ditch inside, not for water, but for the protection of the warriors who occupied it when firing their arrows between the pickets. …

The “Medicine Lodge,” the largest in the village and seventy-five feet in diameter, with four images (sacrifices of different-coloured and costly cloths) suspended on poles above it, was considered by these people as a sort of temple, held as strictly sacred, being built and used solely for these four days’ ceremonies, and closed during the rest of the year.

In an open area in the centre of the village stands the Ark (or “Big Canoe”), around which a great proportion of their ceremonies was performed. This rude symbol, of eight or ten feet in height, was constructed of planks and hoops, having somewhat the appearance of a large hogshead standing on its end, and containing some mysterious things which none but the medicine men were allowed to examine. An evidence of the sacredness of this object was the fact that though it had stood, no doubt for many years, in the midst and very centre of the village population, there was not the slightest discoverable bruise or scratch upon it! …

The O-kee-pa, though in many respects apparently so unlike it, was strictly a religions ceremony, it having been conducted in most of its parts with the solemnity of religious worship, with abstinence, with sacrifices, and with prayer, whilst there were three other distinct and ostensible objects for which it was held.

1st. As an annual celebration of the event of the “subsiding of the waters” of the Deluge, of which they had a distinct tradition, and which in their language they called “Mee-ne-ró-ka-há-sha” (the settling down of the waters).

2nd. For the purpose of dancing what they called “Bel-lohk-na-pick” (the bull dance), to the strict performance of which they attributed the coming of buffaloes to supply them with food during the year.

3rd. For the purpose of conducting the young men who had arrived at the age of manhood during the past year, through an ordeal of privation and bodily torture, which, while it was supposed to harden their muscles and prepare them for extreme endurance, enabled their chiefs, who were spectators of the scene, to decide upon their comparative bodily strength and ability to endure the privations and sufferings that often fall to the lot of Indian warriors, and that they might decide who amongst the young men was the best able to lead a war party in an extreme exigency.

The season having arrived for the holding of these ceremonies, the leading medicine (mystery) man of the tribe presented himself on the top of a wigwam one morning before sunrise, and haranguing the people told them that “he discovered something very strange in the western horizon, and he believed that at the rising of the sun a great white man would enter the village from the west and open the Medicine Lodge.”

In a few moments the tops of the wigwams, and all other elevations, were covered with men, women, and children on the look-out; and at the moment the rays of the sun shed their first light over the prairies and back of the village, a simultaneous shout was raised, and in a few minutes all voices were united in yells and mournful cries. All eyes were at this time directed to the prairie, where, at the distance of a mile or so from the village, a solitary human figure was seen descending the prairie hills and approaching the village in a straight line, until he reached the picket, where a formidable array of shields and spears was ready to receive him. A large body of warriors was drawn up in battle-array, when their leader advanced and called out to the stranger to make his errand known, and to tell from whence he came. He replied that he had come from the high mountains in the west, where lie resided—that he had come for the purpose of opening the Medicine Lodge of the Mandans, and that he must have uninterrupted access to it, or certain destruction would be the fate of the whole tribe. The head chief and the council of chiefs, who were at that moment assembled in the council-house, with their faces painted black, were sent for, and soon made their appearance in a body at the picket, and recognized the visitor as an old acquaintance, whom they addressed as “ Nu-mohk-muck-a-nah ” (the first or only man). All shook hands with him, and invited him within the picket. He then harangued them for a few minutes, reminding them that every human being on the surface of the earth had been destroyed by the water excepting himself, who had landed on a high mountain in the West, in his canoe, where he still resided, and from whence he had come to open the Medicine Lodge, that the Mandans might celebrate the subsiding of the waters and make the proper sacrifices to the water, lest the same calamity should again happen to them.The next moment he was seen entering the village under the escort of the chiefs, when the cries and alarms of the villagers instantly ceased, and orders were given by the chiefs that the women and children should all be silent and retire within their wigwams, and their dogs all to be muzzled during the whole of that day, which belonged to the Great Spirit. I had a fair view of the reception of this strange visitor from the West; in appearance a very aged man, whose body was naked, with the exception of a robe made of four white wolves’ skins. His body and face and hair were entirely covered with white clay, and he closely resembled, at a little distance, a centenarian white man. In his left hand he extended, as he walked, a large pipe, which seemed to be borne as a very sacred thing. The procession moved to the Medicine Lodge, which this personage seemed to have the only means of opening. He opened it, and entered it alone, it having been (as I was assured) superstitiously closed during the past year, and never used since the last annual ceremony. The chiefs then retired to the council-house, leaving this strange visitor sole tenant of this sacred edifice; soon after which he placed himself at its door, and called out to the chiefs to furnish him “four men,— one from the North, one from the South, one from the East, and one from the West, whose hands and feet were clean and would not profane the sacred temple while labouring within it during that day.” These four men were soon produced, and they were employed during the day in sweeping and cleaning every part of the temple, and strewing the floor, which was a concrete of gravel and clay, and ornamenting the sides of it, with willow boughs and aromatic herbs which they gathered in the prairies, and otherwise preparing it for the “Ceremonies,” to commence on the next morning. During the remainder of that day, while all the Mandans were shut up in their wigwams, and not allowed to go out, Nu-mohk-muck-a-nah (the first or only man) visited alone each wigwam, and, while crying in front of it, the owner appeared and asked, “Who’s there?” and “What was wanting?” To this Nu-mohk-muck-a-nah replied by relating the destruction of all the human family by the Flood, excepting himself, who had been saved in his “Big Canoe,” and now dwelt in the West; that he had come to open the Medicine Lodge, that the Mandans might make the necessary sacrifices to the water, and for this purpose it was requisite that he should receive at the door of every Mandan’s wigwam some edged tool to be given to the water as a sacrifice, as it was with such tools that the “Big Canoe” was built. He then demanded and received at the door of every Mandan wigwam, some edged or pointed tool or instrument made of iron or steel, which seemed to have been procured and held in readiness for the occasion; with these he returned to the Medicine Lodge at evening, where lie deposited them, and where they remained during the four days of the ceremony.

Nu-mohk-muck-a-nah rested alone in the Medicine Lodge during that night, and at sunrise the next morning, in front of the lodge, called out for all the young men who were candidates for the O-kee-pa graduation as warriors, to come forward—the rest of the villagers still enclosed in their wigwams. In a few minutes about fifty young men, whom I learned were all of those of the tribe who had arrived at maturity during the last year, appeared in a beautiful group, their graceful limbs entirely denuded, but without exception covered with clay of different colours from head to foot—some white, some red, some yellow, and others blue and green, each one carrying his shield of bull’s hide on his left arm, and his bow in his left hand, and his medicine bag in the rigt. In this plight they followed Nu-mohk-múck-a-nah into the Medicine Lodge in “Indian file,” and taking their positions around the sides of the lodge, each one hung his bow and quiver, shield and medicine bag over him as he reclined upon the floor of the wigwam. Nu-mohk-múck-a-nah then called into the Medicine Lodge the principal medicine man of the tribe, whom he appointed O-kee-pa-ka-see-ka (Keeper or Conductor of the Ceremonies), by passing into his hand the large pipe which he had so carefully brought with him.

Mandan's Medicine Man, 1830г.

Nu-mohk-múck-a-nah then took leave of him by shaking hands with him, and left the Medicine Lodge, saying that he would return to the West, where he lived, and be back again in just a year to reopen the Medicine Lodge.

The Master of the Ceremonies then took his position, reclining on the ground near the fire, in the centre of the lodge, with the medicine pipe in his hand, and commenced crying, and continued to cry to the Great Spirit, while he guarded the young candidates who were reclining around the sides of the lodge, and for four days and four nights were not allowed to eat, drink, or to sleep. By such denial great lassitude, and even emaciation, was produced, preparing the young men for the tortures which they afterwards went through.

Bel-lohk-na-pick

Bel-lohk-na-pick - bull-dance.

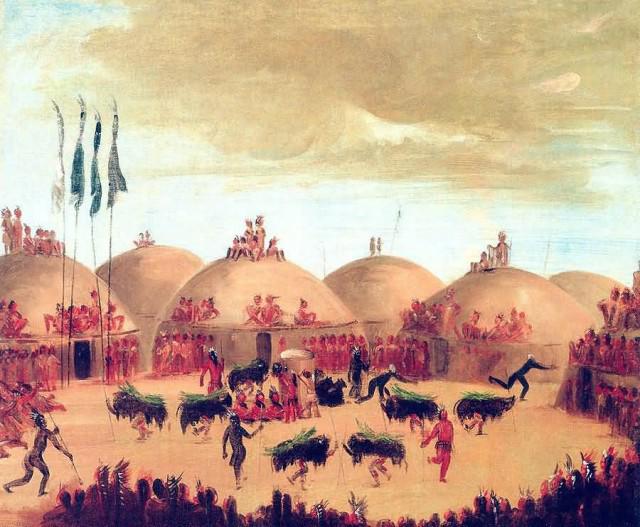

The principal of these, which they called Bel-lohk-na-pick (the bull dance), to the strict observance of which they attributed the coming of buffaloes to supply them with food, was one of an exceedingly grotesque and amusing character, and was danced four times on the first day, eight times on the second day, twelve times on the third day, and sixteen times on the fourth day, and always around the “Big Canoe,” of which I have already spoken. The chief actors in these strange scenes were eight men, with the entire skins of buffaloes thrown over them, enabling them closely to imitate the appearance and motions of those animals, as the bodies of the dancers were kept in a horizontal position, the horns and tails of the animals remaining on the skins, and the skins of the animals’ heads served as masks, through the eyes of which the dancers were looking.

These eight men representing eight buffalo bulls, being divided into four pairs, took their positions on the four sides of the Ark, or “Big Canoe,” representing thereby the four cardinal points; and between each couple of these, with his back turned to the “Big Canoe,” was another figure engaged in the same dance, keeping step with the eight buffalo bulls, with a staff in one hand and a rattle in the other: and being four in number, answered again to the four cardinal points. Two of these figures were painted jet black with charcoal and grease, whom they called the night, and the numerous white spots dotted over their bodies and limbs they called stars. The other two, who were painted from head to foot as red as vermilion could make them, with white stripes up and down over their bodies and limbs, were called the morning rays.

Of men performing their respective parts in the bull dance, representing the various animals, birds, and reptiles of the country, there were about forty, and forty boys representing antelopes—making a group in all of eighty figures and the fifty young men resting in the Medicine Lodge, and waiting for the infliction of their tortures; so that one hundred and thirty persons engaged in these scene.

In the midst of the last dance on the fourth day, a sudden alarm throughout the group announced the arrival of a strange character from the West. Women were crying, dogs were howling, and all eyes were turned to the prairie, where, a mile or so in distance, was seen an individual man making his approach towards the village; his colour was black, and he was darting about in different directions, and in a zigzag course approached and entered the village, amidst the greatest (apparent) imaginable fear and consternation of the women and children.This strange and frightful character, whom they called O-ke-hée-de (the owl or Evil Spirit), darted through the crowd where the buffalo dance was proceeding, alarming all he came in contact with. His body was painted jet black with pulverized charcoal and grease, with rings of white clay over his limbs and body. Indentations of white, like huge teeth, surrounded his mouth, and white rings surrounded his eyes. In his two hands he carried a sort of wand—a slender rod of eight feet in length, with a red ball at the end of it, which he slid about upon the ground as he ran.

On entering the crowd where the buffalo dance was going on, he directed his steps towards the groups of women, who retreated in the greatest alarm, tumbling over each other and screaming for help as he advanced upon them. At this moment of increased alarm the screams of the women had brought by his side O-kee-pa-ka-see-ka (the conductor of the ceremonies) with his medicine pipe, for their protection. This man had left the “Big Canoe,” against which he was leaning and crying during the dance, and now thrust his medicine pipe before this hideous monster, and, looking him full in the eyes, held him motionless under its charm, until the women and children had withdrawn from his reach. In several attempts of this kind the Evil Spirit was thus defeated, after which he came wandering back amongst the dancers, apparently much fatigued and disappointed; and the women gradually advancing and gathering around him, evidently less apprehensive of danger than a few moments before.In this distressing dilemma he was approached by an old matron, who came up slyly behind him with both hands full of yellow dirt, which (by reaching around him) she suddenly dashed in his face, covering him from head to foot and changing his colour, as the dirt adhered to the undried bear’s grease on his skin. As he turned around he received another handful, and another, from different quarters; and at length another snatched his wand from his hands, and broke it across her knee; others grasped the broken parts, and, snapping them into small bits, threw them into his face. His power was thus gone, and his colour changed: he began then to cry, and, bolting through the crowd, he made his way to the prairies, where he fell into the hands of a fresh swarm of women and girls (no doubt assembled there for the purpose) outside of the picket, who hailed him with screams and hisses and terms of reproach, whilst they were escorting him for a considerable distance over the prairie, and beating him with sticks and dirt.

The bull dance and other grotesque scenes being finished outside of the Medicine Lodge, the torturing scene (or pohk-hongas they called it) commenced within, in the following manner.

Pohk-hong

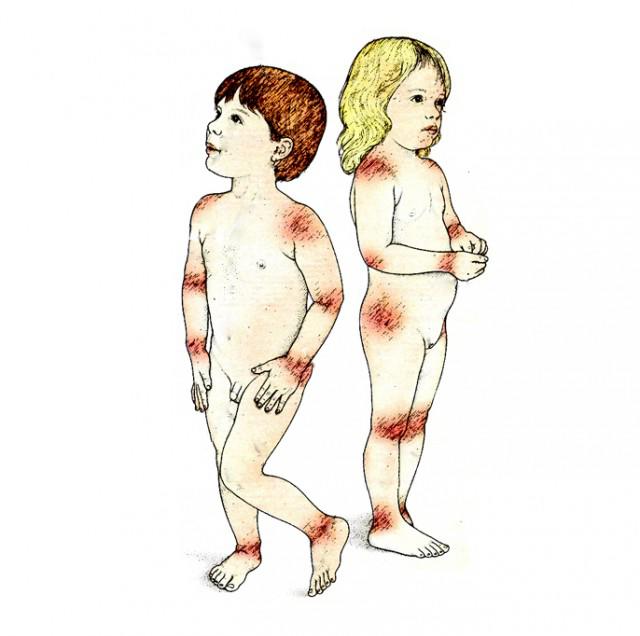

The young men reclining around the sides of the Medicine Lodge, who had now reached the middle of the fourth day without eating, drinking, or sleeping, and consequently weakened and emaciated, commenced to submit to the operation of the knife and other instruments of torture. Two men, who were to inflict the tortures, had taken their positions near the middle of the lodge; one, with a large knife with a sharp point and two edges, which were hacked with another knife in order to produce as much pain as possible, was ready to make the incisions through the flesh, and the other, prepared with a handful of splints of the size of a man’s finger, and sharpened at both ends, to be passed through the wounds as soon as the knife was withdrawn. The bodies of these two men, who were probably medicine men, were painted red, with their hands and feet black; and the one who made the incisions with the knife wore a mask, that the young men should never know who gave them their wounds; and on their bodies and limbs they had conspicuously marked with paint the scars which they bore, as evidence that they had passed through the same ordeal. To these two men one of the emaciated candidates at a time crawled up and submitted to the knife, which was passed under and through the integuments and flesh taken up between the thumb and forefinger of the operator, on each arm, above and below the elbow, over the brachialis externus and the extensor radialis, and on each leg above and below the knee, over the vastus externus and the peroneus; and also on each breast and each shoulder. These cords having been attached to the splints on the breast or the shoulders, each one had his shield hung to some one of the splints: his medicine bag was held in his left hand, and a dried buffalo skull was attached to the splint on each lower leg and each lower arm, that its weight might prevent him from struggling; when, at a signal, by striking the cord, the men on top of the lodge commenced to draw him up. He was thus raised some three or four feet above the ground, until the buffalo heads and other articles attached to the wounds swung clear, when another man, his body red and his hands and feet black, stepped up, and, with a small pole, began to turn him around.

The turning was slow at first, and gradually increased until fainting ensued, when it ceased. In each case these young men submitted to the knife, to the insertion of the splints, and even to being hung and lifted up, without a perceptible murmur or a groan; but when the turning commenced, they began crying in the most heartrending tones to the Great Spirit, imploring him to enable them to bear and survive the painful ordeal they were entering on. This piteous prayer, the sounds of which no imagination can ever reach, and of which I could get no translation, seemed to be an established form, ejaculated alike by all, and continued until fainting commenced.…In each instance they were turned until they fainted and their cries were ended. Their heads hanging forwards and down, and their tongues distended, and becoming entirely motionless and silent, they had, in each instance, the appearance of a corpse. …When brought to this condition, without signs of animation, the lookers-on pronounced the word dead! dead! when the men who had turned them struck the cords with their poles, which was the signal for the men on top of the lodge to lower them to the ground, —the time of their suspension having been from fifteen to twenty minutes. …

In each instance, as soon as they got strength enough partly to rise, and move their bodies to another part of the lodge, where there sat a man with a hatchet in his hand and a dried buffalo skull before him, his body red, his hands and feet black, and wearing a mask, they held up the little finger of the left hand towards the Great Spirit (offering it as a sacrifice, as they thanked him audibly, for having listened to their prayers and protected their lives in what they had just gone through), and laid it on the buffalo skull, where the man with the mask struck it off at a blow with the hatchet, close to the hand.

The young man seemed to take no care or notice of the wounds thus made, and neither bleeding nor inflammation to any extent ensued, though arteries were severed—owing probably to the checked circulation caused by the reduced state to which their four days and nights of fasting and other abstinence had brought them.

Eeh-ke-nah-ka-na

This part of the ceremony, which they called Eeh-ke-náh-ka Na-pick (the last race), took place in presence of the whole tribe, who were lookers-on. For this a circle was formed by the buffalo dancers (their masks thrown off) and others who had taken parts in the bull dance, now wearing headdresses of eagles’ quills, and all connected by circular wreaths of willow-boughs held in their hands, who ran, with all possible speed and piercing yells, around the “Big Canoe”; and outside of that circle the bleeding young men thus led out, with all their buffalo skulls and other weights hanging to the splints, and dragging on the ground, were placed at equal distances, with two athletic young men assigned to each, one on each side, their bodies painted one half red and the other blue, and carrying a bunch of willow-boughs in one hand, who took them, by leather straps fastened to the wrists, and ran with them as fast as they could, around the “Big Canoe”; the buffalo skulls and other weights still dragging on the ground as they ran, amidst the deafening shouts of the bystanders and the runners in the inner circle, who raised their voices to the highest key, to drown the cries of the poor fellows thus suffering by the violence of their tortures.

The ambition of the young aspirants in this part of the ceremony was to decide who could run the longest under these circumstances without fainting, and who could be soonest on his feet again after having been brought to that extremity. So much were they exhausted, however, that the greater portion of them fainted and settled down before they had run half the circle, and were then violently dragged, even (in some cases) with their faces in the dirt, until every weight attached to their flesh was left behind.

This must be done to produce honourable scars, which could not be effected by withdrawing the splints endwise; the flesh must be broken out , leaving a scar an inch or more in length: and in order to do this, there were several instances where the buffalo skulls adhered so long that they were jumped upon by the bystanders as they were being dragged at full speed, which forced the splints out of the wounds by breaking the flesh, and the buffalo skulls were left behind.The tortured youth, when thus freed from all weights, was left upon the ground, appearing like a mangled corpse, whilst his two torturers, having dropped their willow-boughs, were seen running through the crowd towards the prairies, as if to escape the punishment that would follow the commission of a heinous crime.In this pitiable condition each sufferer was left, his life again entrusted to the keeping of the Great Spirit, the sacredness of which privilege no one had a right to infringe upon by offering a helping hand. Each one in turn lay in this condition until “the Great Spirit gave him strength to rise upon his feet,” when he was seen, covered with marks of trickling blood, staggering through the crowd and entering his wigwam, where his wounds were probably dressed, and with food and sleep his strength was restored.… As soon as the six or eight thus treated were off from the ground, as many more were led out of the Medicine Lodge and passed through the same ordeal … and on the occasion I am describing, to the whole of which I was a spectator, I should think that about fifty suffered in succession, and in the same manner.…

It was natural for me to inquire, as I did, whether any of these young men ever died in the extreme part of this ceremony, and they could tell me of but one instance within their recollection, in which case the young man was left for three days upon the ground (unapproached by his relatives or by physicians) before they were quite certain that the Great Spirit did not intend to help him away. They all seemed to speak of this, however, as an enviable fate rather than as a misfortune; for “the Great Spirit had so willed it for some especial purpose, and no doubt for the young man’s benefit.”

After the Medicine Lodge had thus been cleared of its tortured inmates, the master or conductor of ceremonies returned to it alone, and, gathering up the edged tools which I have said were deposited there, and to be sacrificed to the water on the last day of the ceremony, he proceeded to the bank of the river, accompanied by all the tribe, in whose presence, and with much form and ceremony, he sacrificed them by throwing them into deep water from the rocks, from which they could never be recovered: and then announced that the Great Spirit must be thanked by all—and that the O-kee-pa was finished.

full version - americanheritage.com